I want you to take a moment and imagine something: you are a child. Your mother is a baker and your father is a carpenter. You grow up assisting them with their various tasks, sanding wood for a chair here, feeding sourdough starter there, and by the time you get to high school you’re introduced to geometry and chemistry. Parts of these subjects come naturally, as if you almost don’t understand why you know them so well. Other aspects, particularly the reading and homework involved, are very frustrating, and require extra time with the teacher and your peers to understand and accomplish. You share your bemusement about this at the dinner table and your parents shrug it off. These are the garden variety struggles of life at your age. They’ll pass.

But there’s a reason for the bemusement, a source underneath the reality. The aspects of geometry and chemistry that you understand are informed by a lifetime of helping your parents with their vocations. You know the Pythagorean theorem because you’ve helped your father cut wood for tables. You understand moles and titrations because you’ve helped your mother play around with the right ratio of baking soda and yeast. But: you’ve never “learned” the Pythagorean theorem. And you’ve never calculated a titration before. The reason for this confusion is because your experience with these things is poetic rather than taught.

Poetic understanding is hard to come by in this age unless you know where to look for it. As described in James S. Taylor’s landmark book Poetic Knowledge: The Recovery of Education, which I recommend to everyone, the poetic experience is the result of direct interaction with, and thus understanding of, a thing. It means knowing something because you have a tangible, sense-based relation to it, and you have learned about it through use, interaction, experimentation, sharing, responsibility, propriety, imitation, and any relevantly applicable combination thereof. Poetic knowledge manifests itself materially in our world, in the things we make, and in the ways we behave based off the mythos we consume. It is the most influential type of learning there is, but it is often ignored or unknown because it doesn’t fit into the norms of the information age.

A full reckoning with the nature of poetic knowledge will come later. I have only recently finished Taylor’s book and I need more time to digest its insights. Today, I’d like to use a small example of a place where the poetic experience is easily seen and understood to demonstrate how powerful it is: videogames.

Well, let’s be honest, to the extent that videogames have a poetic element to them, they have not been broadly poetic in some time. For the last 20 years, the chief end of the videogame industry has been to find workable revenue models that can be safely stapled to a potent mix of popular intellectual property and addictive gameplay mechanics and then ridden for profit. Many of these models have failed, because they openly chafe against the core poetic appeal of videogames, but the publishers control the purse strings, and that hasn’t stopped them from trying to make them work or blaming their failures on the artists and engineers who actually make the games themselves. Things have been particularly grim in the last eighteen months as the industry has undergone a massive contraction, but this too is a conversation for another time.

Every once in a while, a game comes along that is utterly free and liberated from the patterns of the industry and reminds us why games are so quixotic and popular in the first place. Today, that game is Animal Well, a 2-D exploration platformer released last month for all major platforms.

Animal Well isn’t just a poetic experience, it is a return to the most basic necessities of interactive form and storytelling. It manages to be both carefully and artfully made, with every piece of it placed just so, and startlingly surprising and emergent, in which the player is consistently rewarded for testing and experimenting with its tools and geography. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

We must first answer three questions: What makes a videogame poetic? How does it go about being poetic? Why is it notable that a game would be poetic today?

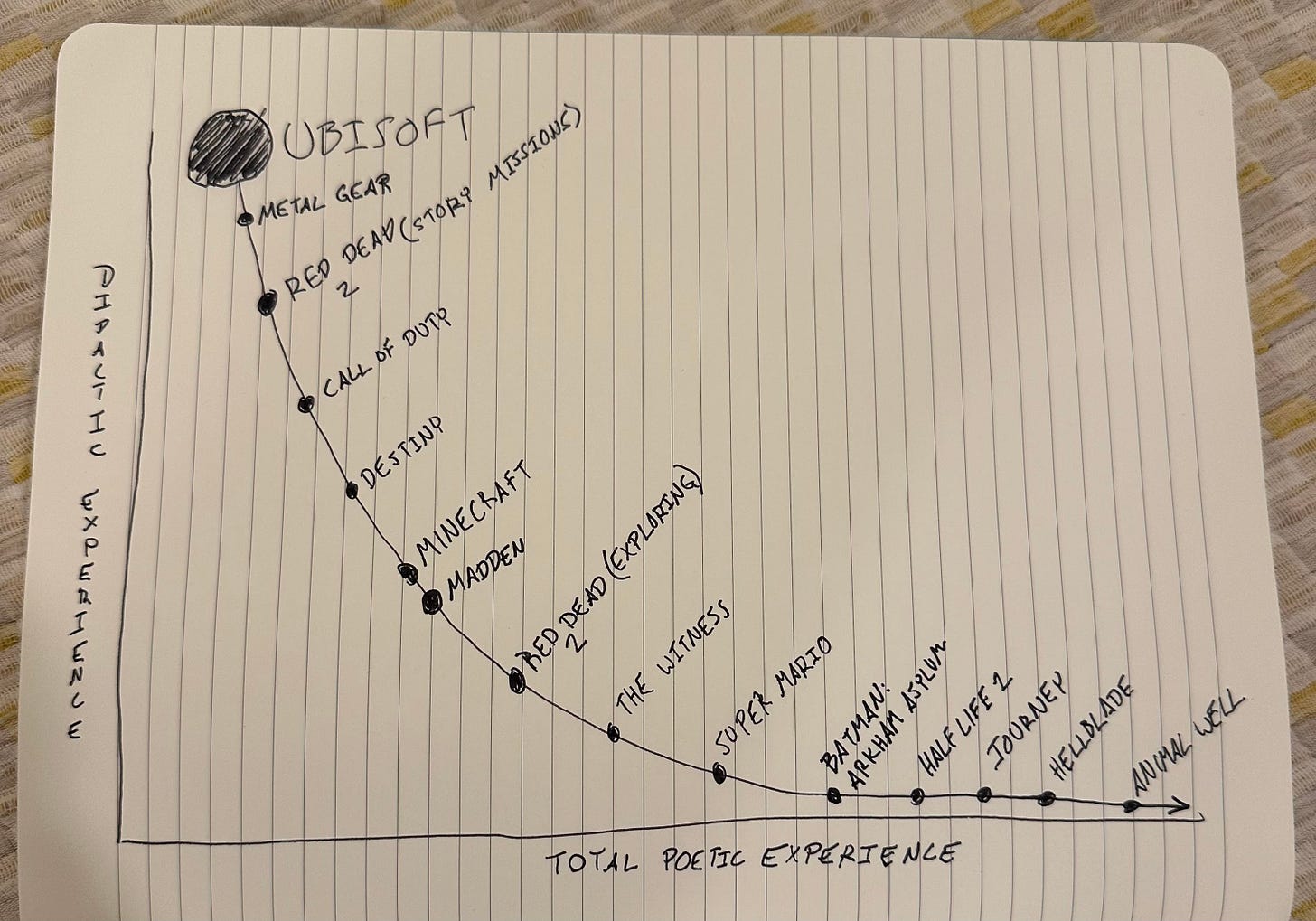

Regarding question 1: The poetic experience of videogames exists on an asymptotic spectrum. All videogames have a poetic element to them, because they have to be interacted with, and interaction requires understanding. However, I’m going to assert here that no videogame can ever be “totally poetic” in the same way that we can have poetic knowledge of things in life, because games are inherently artificial, and the tools needed to establish a sensory relationship with them have to be purpose-made for the task. They construct a space in which to be interacted with, and that interaction requires an interface. In other words, they create an individual type of poetry that has to be experienced according to its own design, not through any natural means. Though many game genres share common design language and control inputs, each game is fundamentally its own artifact, and therefore, some games will be more poetic than others. Generally speaking, a… hold on, let me repeat that for emphasis because if gamers find this they will have opinions, GENERALLY SPEAKING, a game that puts less interface- i.e. menus, tutorials, controller guides, other playing data, etc. -in front of the player is farther down the poetic asymptote than its peers. I present the following graph with a few examples as an aid:

One important distinction here: this does not mean that menu-based games such as turn-based RPGs and 4X strategy games like Dragon Quest and Civilization aren’t poetic. Their interface is part of the poetry of playing them. This must be held as distinct from games that disrupt the player with extraneous or obfuscatory data during the playing experience. Let me illustrate it this way: My favorite example of this distinction is Madden NFL (you’ll note its middle placement in the graph above). If I’m playing Madden and I select plays from the playbook according to the circumstances of the match and my understanding of football? That’s poetic. If I’m playing Madden and just running “Coach’s Suggestion” every time? That’s not poetic. I’m letting the game’s data dictate my interaction with it.

This means that yes, some games can be more or less poetic depending on the settings that are established by the player. Furthermore, I’m not saying there’s a right or wrong to that, or that a game further down the asymptote is inherently more valuable than one that’s higher up; just that this is the nature of videogames and the poetic experience.

Regarding question 2: Videogames engage their poetic state when the player understands them well enough to play them without guidance. Again, we must carefully define our terms. Guidance has to do with understanding how a mechanic works or what the boundaries of play are. It doesn’t mean having the solutions to certain challenges on hand or being directed as to what to do- although such aids are a common attendance when playing games. On the asymptote, games that help players understand their mechanics intuitively and allow them to experiment and push the boundaries of their design, even in ways that produce unintended consequences, will be farther down than their peers.

Regarding question 3: Poetic games are hard to come by these days for two reasons. 1) Devs and publishers want their games to be as appealing as possible to a wide audience, and that often means filling moment-to-moment gameplay with button prompts, tutorial text, and other visual data that tells the player what something is rather than letting them discover it, and 2) the commercial concerns of publishers have been allowed to infiltrate the interface of most games to a hitherto unprecedented degree. Ads for different games or in-game purchases are baked into pause screens now, and every multiplayer game is basically sitting inside an online storefront these days. Extraction from this mode of presentation has become all but impossible because, well, gamers don’t know how to vote with their wallet.

In the broader gaming scene, the aspects of games that we call poetic would be called “immersive,” a shorthand term for how engrossing a game is or how convincing its reality is. But I find this term inadequate now. A videogame has the ability to establish a relationship with its player, in which, if the design allows for it, the player has the ability to influence the space they occupy using the methods the game provides. The game and the player are therefore constantly reacting to one another, and the deepening of that back and forth- the development of muscle memory, the understanding of shortcuts to produce intended outcomes, the knowledge of what to do and what comes next -is more accurately described as poetic than immersive, which brings me back to Animal Well.

Animal Well is not very immersive. It contains very little that the average human can relate to or empathize with. But it is very far down the poetic asymptote. It spurns everything that a game might use to convey a story or instruct a player except its atmospheric, retro-style visuals, its clear and distinct sound effects, and the things the player can do. There is a spare and striking purity to its design in that it enables you to do nothing except explore its world and play with the gewgaws you find. There is no text, there is no narration, there is nothing you can use to orient yourself in its world except whatever is in front of you and the memories you have of everything else you’ve seen on its map. It is as close to raw, unadorned play as videogames can get.

You play as a… thing. A blob? A cartoon mole? A tiny ball of earth? You’re a brown circle with eyes that can jump. You wake up inside of a flower and begin exploring the Animal Well, about which the only thing you can really be sure is that it is subterranean. As you explore, you’ll come across mysterious statues, deal with animals of various sizes and behaviors, find hidden eggs, and use an array of found objects to solve puzzles. There’s no rhyme or reason to any of it, you simply explore and discover for its own sake, and the lack of formal knowledge about what this place is makes the act thrilling.

Animal Well is a game of pointless mysteries concealing delightful revelations. You have no reason to embark upon its journey until you stumble across the one thing- and it’s likely different for every player -that reshapes your understanding of what this world is, what you can do in it, and consequently puts a giant grin on your face and makes you say, “I have to keep going.” Animal Well exists entirely to create and nurture that feeling of wonderful discovery, and it does it all without giving a word of instruction to the player.

This is a revelation in 2024. Videogames haven’t put this kind of trust in players since the days where it wasn’t even occurring to developers. That’s a bit hyperbolic, but Animal Well feels so fresh and ahead of the curve in so many ways simply by going back to simpler, less complex design. Everything about it carries more impact because of its simplicity. Its Eureka! moments are brighter, its triumphs are greater than games with orders of magnitude more production value, and its scares… man. Animal Well is not a horror game, per se, but let me just say… a dachshund has never been so alarming.

This could not have arrived at a more appropriate time. Game execs are fantasizing about how to fit ads in games while they shut down studios that have shipped successful titles. Granted, Animal Well is an indie production and it’s free from most of the concerns of studio development, but any publisher who’s interested in games for more than just money (if that person exists) would do well to look at how Animal Well reveals just how much of modern videogame design is either unnecessary or better served by simply letting the art and sound design do its thing while the player does… whatever comes to mind. I’m sure most devs are already ahead of the curve on this, they just need support from the suits.

Animal Well’s spare, direct frankness with the player and its mechanics (none of which I have mentioned specifically because I don’t want to ruin their surprises) allows the player to form an almost-natural sensory understanding of the game. Though the artifice of the medium remains, this might be farther down the poetic asymptote than anything I’ve ever played, because of the humility of its design. On its own terms, it can only be understood, it can only be known, by playing it. Further, its ultimate goal, its chief pleasure, is the knowledge of knowing it. And sure, there’s already a wealth of content on YouTube and Twitch unveiling its many secrets and quirks, but the game isn’t responsible for that. Unto itself, it is a marvelous set of curios within curios, and I hope its influence spreads wide and deep.

May our Lord illuminate the righteous path He has laid before each of us and compel us to walk it dutifully and with joy.